Postcard Courtesy of Madison Kirkman – M.M.C.C.H.S.

Here’s a rare postcard that appears to be a lithograph of an artist’s impression of a photo taken of the “Denver” on the D.L.&N.W.R.R.

Courtesy of Oil-Electric.com

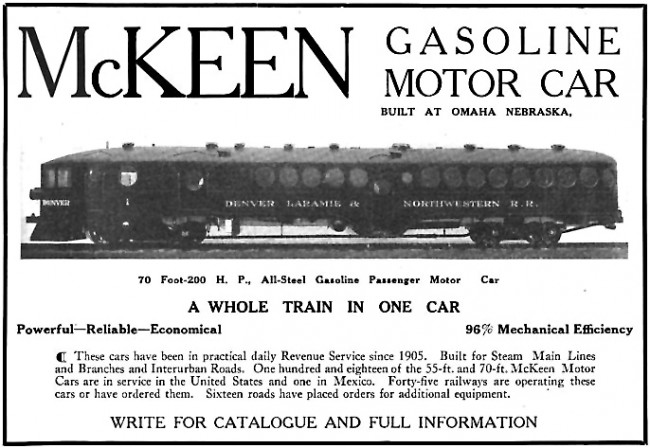

McKeen Motor Car Company Advertisement.

Postcard Courtesy of Madison Kirkman – M.M.C.C.H.S.

McKeen Motor Car M-1 “Greeley.” Photo taken in 1916.

McKeen Motor Car M-1 “Greeley” taken in 1915 in Denver, Colorado.

The Greeley Motor Car weight 40T, carried only 38 passengers. This car was sold to the Great Western Railroad, ran there as M-1, and was later sold to the U.P. and became the second M-4 Motor Car on their Roster.

The Denver Motor Car was just like the Greeley in design, and was sold to the Great Western Railroad as well, and like her sister, went to the U.P., and became M-5. The M-5 was retired in December of 1944. Whether or not the Greeley was scrapped the same year, that is not known.

Photo of the Railroad Crew posing in front of the Denver McKeen Motor Car shortly after arrival from the Factory.

Here one of the cars ran into a washout bridge, left with just the rails to hold the weight of the motor car. In the photo above it shows railroad crew using railroad ties to try to support the weight of the motor car in an attempt to save the car from more damage.

The Life of the D.L.&N.W.R.R. by the Colorado Encyclopedia

The Denver, Laramie, & Northwestern Railroad Company (DL&NW) was a small firm that planned to link Denver and Seattle by rail in the early twentieth century. The company’s history serves as an example of the pitfalls of running a small railroad company in the western United States at a time when giant railroad conglomerates dominated the national scene. Today, the railroad is defunct, surviving only in museum collections, but its legacy lives on in the small towns established along its right-of-way.

Incorporation and Beginnings

The Denver, Laramie, & Northwestern Railway Company (as the DL&NW was originally known) was incorporated in Wyoming on March 5, 1906, with the ambitious scheme of building a line from Denver nearly straight to Seattle, touching the southwest corner of Yellowstone National Park. A basic problem with the route was that it paralleled the Union Pacific’s main line north out of Denver and cut through territory already served by the Great Western Railway and the Colorado & Southern (C&S). The DL&NW was financed through the local sale of common stock at a time when the large banking houses of Wall Street financed most railroads. The DL&NW may have challenged conventional wisdom regarding railroad financing, but attorney John D. Milliken, its leading principal investor, was highly experienced in railroad matters; Milliken served the Union Pacific for twenty years as legal counsel and the Rock Island Railroad for a dozen years in the same capacity.

The DL&NW was headquartered in Laramie but had offices in Denver. The articles of incorporation limited construction in Colorado to approximately 100 miles, with an additional 350 miles diagonally across Wyoming to Montana. The Colorado portion of the planned route followed the South Platte River north along its west bank to what is now the town of Milliken, southwest of Greeley. At this point, the original plan called for the main line to turn northwest to Fort Collins, Virginia Dale, and Laramie.

By May 1908, there were 1,600 small stockholders, and this grassroots effort yielded enough capital to begin construction. Work began at a point immediately south of Utah Junction, about three miles north of downtown Denver. At first, construction was relatively easy, as the land along the west bank of the South Platte was flat, dissected by only a few streambeds. The only significant project was a long, low trestle across Clear Creek. Like many other railroads, the DL&NW got into the real estate business along its right-of-way. With the formation of the Denver-Laramie Realty Company, towns were planned at locations along the rail line, with the hope that they would become trade centers in the predominantly agricultural regions of northern Colorado. The first town was Cline (later, Welby), about seven miles north of Denver. Next was Wattenberg, some twenty-two miles north of Denver. Seventeen miles farther, the town of Fort St. Vrain was established adjacent to the location of the old trading post.

Trouble with Other Companies

The first significant town on the main line was Fort Collins, and the powerful Union Pacific worked to keep the DL&NW from reaching the city. The rival road began work on its own branch between Denver and LaSalle, known as the Dent Branch, in 1909–10. In 1911 the Union Pacific laid track from Dent, seven miles west of LaSalle, twenty-five miles to Fort Collins. At one point, the Union Pacific intentionally placed its right-of-way to block the DL&NW. At the same time, the DL&NW was struggling to come up with sufficient funds to pass through Greeley. Eventually, a group of Greeley businessmen solved this problem by incorporating the Greeley Terminal Railway Company, which would purchase rights-of-way, pay for a little more than a mile of track within the city limits, and build a modest depot. The Greeley Terminal leased its track to the DL&NW for ninety-nine years and the DL&NW was able to reach Greeley.

The DL&NW also found itself opposed by the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad, which wanted to build a route from its main line at Hudson north to Greeley; connect with its subsidiary, the C&S; and then proceed northward to Fort Collins and Cheyenne. But the DL&NW’s right-of-way blocked Burlington’s access to Greeley, and the company discarded its plan. The smaller DL&NW notched a victory, but not without headache.

Compounding all of this competition was a light rail line designed to connect all major communities in northern Colorado. It had already acquired a right-of-way from Greeley to the DL&NW company town of Milliken, graded its line between Greeley and Evans, and planned to use a series of hydroelectric dams throughout the Front Range to power the trolley cars. Greeley’s city council realized that unless it gained some control over the many rail companies, competing railroads would enter the town at odd angles and create havoc with traffic patterns. The council elected to confine all railroad construction to Seventh Avenue, the east side of which was already occupied by the Union Pacific main line. Neutrality among the rail companies proved impossible to enforce because the mayor sided with the DL&NW and many prominent citizens had invested in the DL&NW companion line, the Greeley Terminal. Following a newspaper campaign, the DL&NW was awarded the west side of Seventh Avenue and the Burlington got the center. Crowding was avoided because the Burlington never followed through on its plan to extend into Greeley and the light rail line went out of business before the streetcar line was completed.

DL&NW Service

Despite ongoing obstacles and difficulties, the DL&NW began scheduled rail service from Denver to Milliken on January 6, 1910. The DL&NW now set its sights on raising money to lay 750 miles of track to reach Boise, Idaho, filing new incorporation papers in Wyoming on February 9, 1910. The line would now run through central Idaho via Pocatello, Twin Falls, and Boise and terminate in Vancouver, British Columbia, rather than Seattle. The name also changed from the Denver, Laramie, &Northwestern Railway Company to Railroad Company. Not a single director from the old company was retained. It was imperative at this time for the DL&NW to proceed beyond Greeley, and work began on the eleven-mile link from Greeley northwest to Severance.

The DL&NW’s original rolling stock included four former Union Pacific locomotives, which were antiques even then. In January 1909, the DL&NW purchased a handsome engine from the Midland Valley Railroad, calling it Number 101. In 1910 the company bought two more locomotives, giving it one locomotive for every eight miles of existing track. The DL&NW engines were painted red and became known as the “Red Torpedoes.” Each could travel from Denver to Greeley in one hour and fifty-five minutes, with sixteen stops and three round-trips daily. But with its meager fifty-six miles of track, the DL&NW often did not have enough traffic to cover its operating costs. In early 1912, after suffering heavy losses for two years, president Charles Scott Johnson attempted a refinancing of the struggling railroad. As investors watched their money slip away, the stockholders called for a change of management, and Milliken and Johnson were forced to resign. In a matter of weeks, both the DL&NW and its holding company entered receivership.

Receivership and Closure

At the receivership hearing for DL&NW on June 12, 1912, Judge Harry C. Riddle of Denver District Court appointed his bailiff, Marshall B. Smith, as the railroad’s receiver, entrusted to watch over the DL&NW on behalf of stockholders. Despite a complete lack of any applicable experience in such endeavors, Smith and his brother, Clinton, managed to keep the DL&NW operating for another five years. During its final year, the railroad even turned a meager profit for the first time in its existence. Wages and salaries were cut across the board and resulted in the mass resignation of the entire traffic department. All grading contracts were canceled and no payments were made on any issued bonds. No taxes were paid either, and the railroad defaulted on all of its debts to equipment suppliers.

The court issued a decree of foreclosure in 1915 for the sale of the DL&NW, but it took considerable effort to actually sell the line, in May 1917, for the amount owed its creditors—some $215,000. Investor losses were calculated at $26.7 million. Shippers protested that the DL&NW’s closure would negatively impact their business. The Great Western Sugar Company presented the strongest argument, noting that some 70,000 tons of sugar beets would rot in the ground for lack of transportation. To save its crop, the company bought twenty-eight miles of track north and south of Milliken, plus two locomotives, four days before the end of service. At 9:10 pm on September 2, 1917, the last DL&NW train ran from Denver to the Greeley Terminal depot. In a few weeks’ time, rails, ties, and telephone poles were removed from the portions of the line not sold to Great Western Sugar.

Some vestiges of the long-struggling DL&NW survive today. The town of Milliken is healthy and Wattenberg and Welby remain on some maps. The Butte Royal Tunnel, now on private property, can be reached from US Route 287 near Virginia Dale. Until the 1970s, a hand-decorated safe once owned by the DL&NW rested in Great Western Sugar’s Loveland depot. By the 1980s, all DL&NW track had been removed except for a hundred or so feet in Milliken. The DL&NW’s Milliken depot was sold to a Great Western Sugar agent and moved to Milliken’s residential area. The Wattenberg depot, though modified, stood for many years near the abandoned railway grading. The smallest remaining remnant of the DL&NW is a switch key, held in a private collection.

Adapted from Kenneth Jessen, “The Denver, Laramie & Northwestern: What a Way to Run a Railroad,” Colorado Heritage Magazine 13, no. 3 (1993).